ADS:

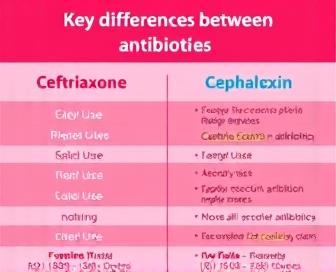

Ceftriaxone VS Cephalexin - Antibiotics Comparison Guide

The selection of the appropriate antibiotic can determine successful treatment and minimize its side effects in bacterial infections. Various antibiotics are commonly used to treat infections of all types, including ceftriaxone (a zikader) and cephalexin (an antibiotic that can work). Despite being classified under the cephalosporin class, the two drugs exhibit notable differences in their chemical structure, pharmacokinetic properties, intended lethal dose forms of administration, indication or warning signs, and potential side effects.

Ceftriaxone is presently the third-generation cephalosporin that exhibits greater activity against Gram-negative bacteria than its forerunners. It has a high degree of penetration into tissues, fluids, and organs such as the lung parenchyma (eutrophic nervous system), the pleura, which holds blood cells in the heart, or the pericardium, but also contains synovial fluid, which is highly potent when applied intravenously. This is especially useful in outpatient settings where the long half-life allows for less frequent dosing. Unlike other antibiotics, cephalexin is a first-generation cephalocarin with fewer antimicrobial capabilities, and it is particularly effective against Gram-positive bacteria.

Both ceftriaxone and Cephalexin are used as treatments for different infections. Ceftriaxone is often prescribed as a treatment for severe infections such as meningitis, endocarditis (on the tongue), sepsis from large distention or in close proximity to the head, pneumonia, and/or osteomyelitis because it effectively targets resistant Gram-negative pathogens like Pseudomonas ivyenii and Enterobacteriaceae. Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), urinary tract infections, and respiratory infections are commonly treated with Cephalexin as a first-line treatment, but not all.

Our ceftriaxone and Cephalexin comparison guide focuses on the differences between these drugs, which include their mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetic characteristics, adverse effect characteristics (DACM), as well as their clinical applications. These distinct characteristics help healthcare providers decide which type of antibiotic to prescribe to individual patients and when appropriate, based on the specific infections they are treated for, the severity levels of the infections that were treated with it, etc.

Ceftriaxone vs Cephalexin Comparison Guide

Healthcare professionals should compare ceftriaxone and cephalexin to determine which treatment is more effective. The two antibiotics are classified as cephalosporins and share some common aberrant but distinct properties.

As a broad-spectrum antibiotic, Ceftriaxone is particularly effective against gram-negative and some gram-positive bacteria, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and HaEmophilus influenza. Infections such as meningitis, septicemia, menorialitichia, and gonorrhea are of notable effectiveness.

In comparison, cephalexin has a more restricted range of activity, with its primary focus being on targeting gram-positive cocci, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcal pyogenes, and methicillin-susceptible S. aurea (MSSA). Typically, it is prescribed for treating skin infections, bone and joint infections like emphysema, urinary tract infections such as lacerated or uncoated heels, and pharyngitis.

The dosage requirements for each antibiotic are notably distinct. Typically, cephalexin is orally administered at doses of 250 to 500 mg every 6-12 hours, and Ceftriaxone is given intravenously/introduced (usually) as powder or injection into the muscles; however, cebuexone (1 once per day, sometimes) with acetylcellulose—the active compound [Ceftrexon] taken orally or otherwise.

The two medications exhibit a common gastrointestinal upset profile, with side effects such as diarrhea or nausea. In spite of this, cephalexin is less likely to cause anaphylaxis, and as a result, the longer half-life of ceftriaxone and increased systemic exposure make it more susceptible to allergic reactions.

Due to these distinctions, healthcare providers must take into account the patient's specific illness (e.g., cough or soreness), antibiotic susceptibility patterns, and individual factors such as age, weight, renal function, etc. when deciding whether to prescribe ceftriaxone or cephalexin. Identifying their particular attributes empowers clinician-administered treatments, leading to more effective outcomes for patients with different infections.

Antibiotic Properties and Effects

Cephalexin and ceftriaxone are two types of cephalosporin antibiotics that have some common features but distinct distinctions. Antibiotics act as a barrier between cells and wall synthesis in bacteria, leading to cell death. The drug interactions are bactericidal, which implies that they target vulnerable bacteria rather than hindering their growth.

Featuring strong beta-lactamase resistance, ceftriaxone is effective against both Gram-1 and Gram-negative pathogens, as well as the majority of which are multidrug-resistant. Its extended half-life enables daily administration, simplifying treatment plans and improving patient comfort. On the flip side, cephalexin is less powerful than ceftriaxone and has a narrower antimicrobial activity, being primarily effective against Gram-positive cocci (bacteria) and some Gram–negative rods.

Despite their safe and effective use, both antibiotics are recommended to be used as directed, but ceftriaxone is more likely to cause infusion reactions and thrombophlebitis due to its high concentration and volume. In individuals with heightened levels, Cephalexin is more likely to cause gastrointestinal disturbances like nausea and diarrhea, particularly at high doses or in those who are highly sensitive. As with any antibiotic, prolonged use can lead to the emergence of resistant bacteria, and overuse may contribute to the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance.

Choosing between ceftriaxone and cephalexin is crucial for doctors because they must take into account the unique characteristics of each patient, their medical history, and whether they are taking either directly or in combination with other agents. Moreover, the decision should take into account local antibiological markers (antibiograms), potential drug interactions, and the patient's tolerance to the medication.

Dosage and Administration Methods

Cephalosporins, including ceftriaxone and cephalexin, necessitate precise dosage administration and administration. Understanding the appropriate dosage of antibiotics is essential in successfully combating bacterial infections.

Ceftriaxone Dosage and AdministrationIntravenous, intramuscular, and oral preparations are the forms in which Ceftriaxone is sold. The recommended dosage of 2 grams of ceftriaxone for adults and children weighing more than 50 kg, given every 12-24 hours by IV or oral injection, is intended for serious infections. Depending on the age and weight of the child, the pediatric dosage range is as follows: neonates given every 8 hours or every 12 hours (50-80 mg/kg/dose for one month), infants (0–11 months old) fed every 5 minutes, and children under 13 years of age given 50-50 mg2/kg daily at any rate of 60 minutes. Dozens of 500 mg to 750 mg per day are commonly given as oral Ceftriaxone.

Cephalexin Dosage and AdministrationAdults and children can only consume Cephalexin in oral tablet or capsule form. A daily allowance of 250-500 mg orally every 6-8 hours is the recommended dosage for adults and children aged one year and above, with a maximum of 4 grams per day. Individuals with impaired renal function may need to modify their dosage.

A strict dosing schedule for ceftriaxone and Cephalexin is necessary in order to prevent antimicrobial resistance, which can result in a lack of efficacy. The recommended dosages for medications are to be taken at the same times each day, as directed by a healthcare provider, and not to double or skip doses.

Treatment Applications and Indications

Ceftriaxone and cephalexin are both cephalosporin antibiotics used to treat a wide range of bacterial infections. These two drugs have different treatment applications and indications, ranging from broad spectrum activity to mode of administration, various dosage regimens (including hydrochloric acid), and various patient populations.

The most common type of intravenous (IV) medication is ceftriaxone, which is indicated for severe infections such as pneumonia, meningitis, and septicemia, as well as endocarditis. A wide variety of Gram-negative pathogens, including Pseudomonases and E coli, as well as some Gram–positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptoccobacter pneumoniae, are included in its broad coverage. Ceftriaxone is especially useful for infections contracted in hospitals or other healthcare facilities.

Cephalexin, on the other hand, is primarily used for less severe infections that can be treated with oral administration, such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), skin and soft tissue infections, bone and joint infections, and respiratory tract infections like bronchitis. While ceftriaxone has a wider range of activity, it is more effective against specific Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Community-acquired infections can be managed with Cephalexin outside of the hospital.

In general, ceftriaxone and cephalexin are used for severe or complex infections that require IV treatment, with cephalyxin being used instead for milder infections where antibiotics can be administered orally. In determining which cephalosporin to prescribe, doctors will consider factors such as the patient's condition and the severity of the infection, as well as potential allergies.

Potential Side Effects and Precautions

Like all antibiotics, ceftriaxone and cephalexin can cause side effects in some people. The mechanism of action of these drugs is the disruption of the bacterial cell wall, which can also impact the cells and tissues within the body. The potential complications and their severity differ based on individual factors, including individual tolerance, the amount administered, treatment duration, and relevant health conditions.

Gastrointestinal issues like diarrhea, nausea resulting in vomiting and abdominal pain, as well as stomach cramps that may occur after taking ceftriaxone or cephalexin are common side effects. A weakened gut microbiota can lead to antibiotic-related colitis in rare cases. Side effects include skin and mucous membranes, ranging from mild to severe with a minor amount of rash or itching; the symptoms may also include Stevens-Johnson syndrome (a type of contagious non-eating dead mice) or toxic epidermal necrolysis.

- Tell your doctor if you encounter any persistent or unusual side effects while taking ceftriaxone or cephalexin.

To ensure that you are taking the right antibiotic and not just the flu, make sure to tell your doctor if you have any medical conditions or already have allergies. Certain medications can increase the likelihood of causing complications, including:

- Those with renal impairment since ceftriaxone and Cephalexin both pass through the kidneys.

- People who have previously suffered from liver disease, due to high doses or long-term use, are at an elevated risk of developing liver toxicity.

- Oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy may interfere with the effectiveness of antibiotics.

Prior to finishing the antibiotic regimen prescribed by your doctor, it is crucial to maintain completeness of antibiotic therapy, even if symptoms improve. The occurrence of an early cessation may cause bacteria to relapse or develop resistance, which could make it more difficult to treat in the future.

We recommend you read it

We highly recommend reading these three pages to gain additional knowledge about cephalexin.

- Examine the durability of cephalexin.

- Obtain information on over-the-counter Cephalexin.

- Understand if cephalexin is used for urinary tract infections.